Flitting effortlessly between treetops, a young man faces off against a nefarious opponent as others—including his beloved—watch with concern. The two fighters defy terrestrial physics, flying from branch to branch in an exhilarating display of combat mastery. This is the sort of scene I grew up watching on screens both small and large—a deadly dance that could be plucked from Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, House of Flying Daggers, or really, any martial arts film where two rivals are determined to destroy each other in mid-air while also having a sharp exchange of words.

In the same way that Star Wars defined a generation of Hollywood sci-fi blockbusters, there’s a common ancestor in the world of martial arts pop culture. The cinematic qualities of the iconic “flying while fighting” trope were popularized by Jin Yong—the pen name of Chinese author, journalist, screenwriter, and film director Louis Cha—who passed away in 2018. Through his fiction, he left a literary legacy that combined film techniques like flashbacks, fast cuts, and bold changes in perspective, creating a new visual foundation for martial arts today. Many of his scenes have become familiar visual flourishes in kung fu movies, and a distinctive way of telling stories in an age-old Chinese genre: wuxia, the realm of martial heroes.

But much of the wuxia we know today was defined by a series that remains little known outside of Chinese pop culture: Jin Yong’s Condor Trilogy—Legend of the Condor Heroes, The Return of the Condor Heroes, and The Heaven Sword and Dragon Saber. Ask a Chinese person if they’ve heard of these stories or characters, and the answer will be most likely yes. Ask a Chinese person in a diaspora community the same, and they’ve probably absorbed some version or snippet of the Condor stories through TV or games. If you’re a fan of the Wu-Tang Clan, their name is a nod to the Wudang Sect, which appears in the third Condor book.

Today, wuxia has filtered out into mainstream pop culture, from the wildly underrated AMC wuxia series Into the Badlands to Stephen Chow’s action-comedy hit Kung Fu Hustle. The former portrays an alternate universe of roving martial arts warriors who pledge allegiance to feudal liege lords—a familiar trope within the wuxia genre that draws broadly from the Chinese folk stories and historical fiction that Jin Yong popularized. In Kung Fu Hustle, the main antagonists—the Landlord and Landlady—jokingly refer to themselves as Yang Guo and Xiaolongnu, a pair of lovers from Return of the Condor Heroes who endure various hardships during their relationship.

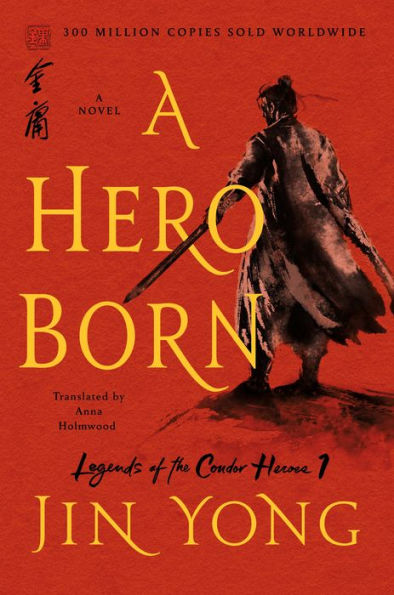

In 2018, for the first time in history, the Condor books were translated to English in a set of four volumes—the first book, A Hero Born, was translated by Anna Holmwood and released in 2018, and the second, A Bond Undone, was translated by Gigi Chang and released in the US in March; Holmwood and Chang both worked on the third book, A Snake Lies Waiting. Work on the fourth is underway.

Buy the Book

A Hero Born

Set in the 1100s, the Condor Heroes trilogy tells intimate, personal stories against a larger sociopolitical backdrop of the Han Chinese trying to repel invading Manchu (or Juchen) forces from the north. Everything begins with a simple, old-fashioned pact made between two friends—depending on their future children’s genders, their kids should either become sworn siblings or get married. Unfortunately, as fate has it, their sons—Guo Jing and Yang Kang—grow up oblivious to their fathers’ wishes. The series features a huge ensemble cast of characters, including “The Seven Freaks of the South,” known for their fighting skills and idiosyncratic personalities, the powerful but disgraced couple “Twice Foul Dark Wind,” and the legendary Quanzhen Sect, based on real Taoists who took part in the Jin-Song wars. All the while, the main thread of the story follows the lives (and subsequently, descendants) of Guo Jing and Yang Kang—the two men who would have been sworn brothers.

Chang first read the Condor Heroes novels at the tender age of 10. This sort of childhood reading fuels a primordial urge to chase an adventure, and though Chang and I only met in 2018, we both grew up chasing the same one. Much like my childhood in Singapore, Chang’s childhood in Hong Kong was also defined by at least one Condor TV series. “Everyone at school watched it and we talked about it, we were all reading it… you know how everyone is talking about this one television show? It’s like when Game of Thrones was on and the whole world is about it—it was like that in the 90s,” Chang recalled. “Growing up in Hong Kong, martial arts fiction is a big deal anyway… there are either cop stories, gangster stories, or martial arts, but it’s pretty much all the same, it’s all men and women fighting… and then you have to bust some bad guys and help the people in need. It’s all the same story.”

First published in 1957, Legend of the Condor Heroes took form as a serialized story in Hong Kong. Since then, its dramatic depictions of life in the ancient Jin-Song era have been adapted into films, TV series, video games, role-playing games, comics, web fiction, and music across China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan; many of the ‘80s and ‘90s shows were a television staple for kids who grew up across the region, including memorable productions by Hong Kong’s legendary Shaw Brothers Studio. One of the most beloved adaptations was Eagle-Shooting Heroes, a madcap comedy film with Hong Kong’s finest actors—Tony Leung Chiu-Wai, Leslie Cheung, Maggie Cheung, Jacky Cheung, and Carina Lau—many of whom also starred in Wong Kar Wai’s very different dramatic adaptation, Ashes of Time (some of whom played the same exact roles). Another popular remake was The Kung Fu Cult Master, a 1993 film starring Jet Li and Sammo Hung—made in the over-the-top vein of many 80s Hong Kong wuxia films.

In the 1980s, a fantastically popular take on Return of the Condor Heroes—arguably the most romantic of the three books—aired in Hong Kong, starring Idy Chan as the formidable fighter Xiaolongnu; this role was also played by Liu Yifei, who now stars in Disney’s delayed live-action remake of Mulan. The white-clad character became a popular blueprint for martial arts heroines, including Zhang Ziyi’s character Jen in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. Today, the Condor Heroes legacy continues. In 2018, The Hollywood Reporter stated that singer, actress, and casino heiress Josie Ho had purchased the mainland rights to Jin’s work in China, with the goal of transforming them into Marvel-style blockbuster franchises.

With a built-in combat system and mythology, it’s natural that Condor Heroes is also a huge influence in games. In 1996, Heluo Studios released a role-playing action game called Heroes of Jin Yong, which sees the player transported back in time to ancient China, where they must learn martial arts. It was one of the first Jin-inspired games, but certainly not the last; in 2013, Chinese mobile game giant Changyou.com snapped up the adaptation rights to 10 Jin Yong titles. There have been a slew of Condor Heroes-inspired titles (of varying quality) since then, like the mobile game Legend of the Condor Heroes that was released in 2017 for the book’s 60th anniversary. The Scroll of Taiwu, a martial arts management role-playing game, has sold well over a million copies on Steam. In an interview with SCMP, the game’s developer, Zheng Jie, said, “As long as it’s wuxia, people will feel reluctant to accept a game if it doesn’t include some of Jin Yong’s influence. His work will be adapted over and over.”

Jin Yong wasn’t the first to popularize wuxia, but according to Chang, he was the first to infuse the world of kung fu with narrative and history. “Chang attended a Jin Yong conference last October, where attendees discussed how martial arts characters have always existed in Chinese fiction and theatre—perhaps most famously, a group of outlaws depicted in the 14th century novel Water Margin. And while Water Margin may have been the first big martial arts work of its kind, Jin Yong’s ability to marry visual storytelling techniques with this longstanding genre of fiction helped to make it more accessible and enjoyable for a wider spread of readers. “[Jin Yong] inserted flashbacks, use of filmic dialogues as well as ‘camera’ angles—so you read as if you’re watching a movie,” Chang explained. “Lots of fast cuts, lots of flipping between perspectives, you often switch between narrative to individual character’s point of view, like a cinematic experience.”

The Condor books exist in this theatrical, often violent world of wulin—roaming martial arts heroes who (mostly) followed principles set by their mentors, mastered different styles of kung fu, and often dispensed their own form of justice in the course of their adventures. In the west, Condor Heroes has been most famously described as “The Chinese Lord of the Rings,” although there are far more relevant comparisons with the sly social commentary of Jane Austen. There’s just as much detail about social manners in the reflections of Cyclone Mei as there are fantasy elements built up around her seemingly superhuman powers; her memories reveal much about her experience of propriety as a young woman, as well as etiquette and education within the martial arts system. In Jin Yong’s imagination, his characters practiced a unique hybrid of individualism as well as Confucian values, which dictated how people related to one another in society—student and teacher, for instance, or father and son. “Most of the stories are set in a turbulent time in history,” Chang said, “where characters, apart from their own troubles, are facing bigger decisions about the changes in the state or society.”

“Jin Yong’s characters generally tend to be free—completely so—not serving anyone but their beliefs and ideas. They want to serve their country and people, but not necessarily within the system, but parallel to the system,” Chang explained. “Most of the stories are set in a turbulent time in history, where characters, apart from their own troubles, are facing bigger decisions about the changes in the state or society.”

Of course, there’s much more to the wuxia genre than Jin Yong—there’s also Gu Long, who drew inspiration from western literary narratives and writing styles for his own wuxia stories, and Liang Yusheng, whose work was adapted into the 2005 Tsui Hark series Seven Swordsmen. But through the Condor Trilogy, Jin Yong developed a distinctively cinematic approach that gave its stories and characters a million extra lives in other media, far more so than its peers. Now with the series’ English translation, it’s finally possible for non-Chinese speaking readers to explore the original source material that gave us, quite arguably, the modern blueprint for a universe of wuxia entertainment.

Extended excerpts from A Hero Born are available here.

Alexis Ong is a freelance culture journalist with weak ankles who mainly writes about games, tech, and pop culture. Her work has appeared in The Verge, Polygon, Kotaku, Rock Paper Shotgun, VICE, Dazed Digital, and more; soft spots include science fiction, internet archaeology, comics, boxing, and old games. You can find her at her website or on Twitter.